Why Gratitude Might Be Hurting Your Recovery (And How to Fix It)

You've probably heard it a thousand times: Be grateful for what you have. Others have it worse. Focus on the positive.

And maybe you've nodded along while something inside you screamed. Because here's the thing—gratitude, when practiced the wrong way, can actually harm your recovery.

The Problem with "Just Be Grateful"

Let me be clear: authentic gratitude has real benefits. Research shows it can improve psychological functioning, physical health, relationships, and career development (Confino et al., 2023). People who practice genuine gratitude tend to experience more positive emotions, demonstrate prosocial behaviors, and cope more effectively with both everyday events and traumatic experiences (McCullough et al., 2002).

But there's a difference between true gratitude and the forced, performative kind that recovery spaces sometimes push on us.

True gratitude comes from awareness of good things in your present life and new experiences. It's heartfelt, authentic, and allows for the right amount of thankfulness to maintain mental health. No one can force you to have it (Davis, 2021).

False gratitude is insincere and inauthentic—it happens when you feel pressured to express thankfulness you don't actually feel, often because someone expects it from you. Being coerced into gratitude as a child can lead to mixed-up feelings and difficulty with healthy relationships in adulthood (Davis, 2021).

Reverse gratitude shows up when you compare your circumstances to others: At least I'm not homeless. At least I didn't lose everything. While this seems positive, it can lead to judgmental thinking about yourself and others (Davis, 2021).

Survival gratitude is perhaps the most insidious form—and many of us learned it before we could even name it.

The Gratitude We Were Trained to Feel

Some of us grew up in homes where we were expected to feel grateful for having our most basic needs met. Food on the table. A roof overhead. Clothes on our backs. These weren't treated as a child's birthright—they were framed as favors we should be thankful for.

You should be grateful I put food in your mouth. You should be grateful you have a place to sleep.

Here's the truth: taking care of a child is not doing them a favor. It's the bare minimum responsibility of a caregiver. Children don't owe gratitude for survival. They deserve care simply because they exist.

But when we're conditioned in childhood to feel indebted for basics, something breaks in how we see ourselves. We internalize a toxic message: My needs are a burden. I don't deserve to have them met. I should be grateful anyone tolerates me at all.

This survival gratitude follows us into adulthood. We struggle to ask for what we need—physically, emotionally, relationally—because somewhere deep down, we still believe we're asking too much. We over-thank people for normal kindness. We stay in situations where we're treated poorly because at least our basic needs are being met, and isn't that enough? Shouldn't we be grateful?

No. You deserved unconditional care as a child, and you deserve to have your needs met now—without apology, without excessive gratitude, without feeling like a burden.

If this resonates, know that unlearning survival gratitude takes time. It means recognizing that your needs are valid, not negotiable. It means understanding that healthy relationships don't require you to grovel for basics. And it means extending to yourself the unconditional care you should have received all along.

When Gratitude Becomes Harmful

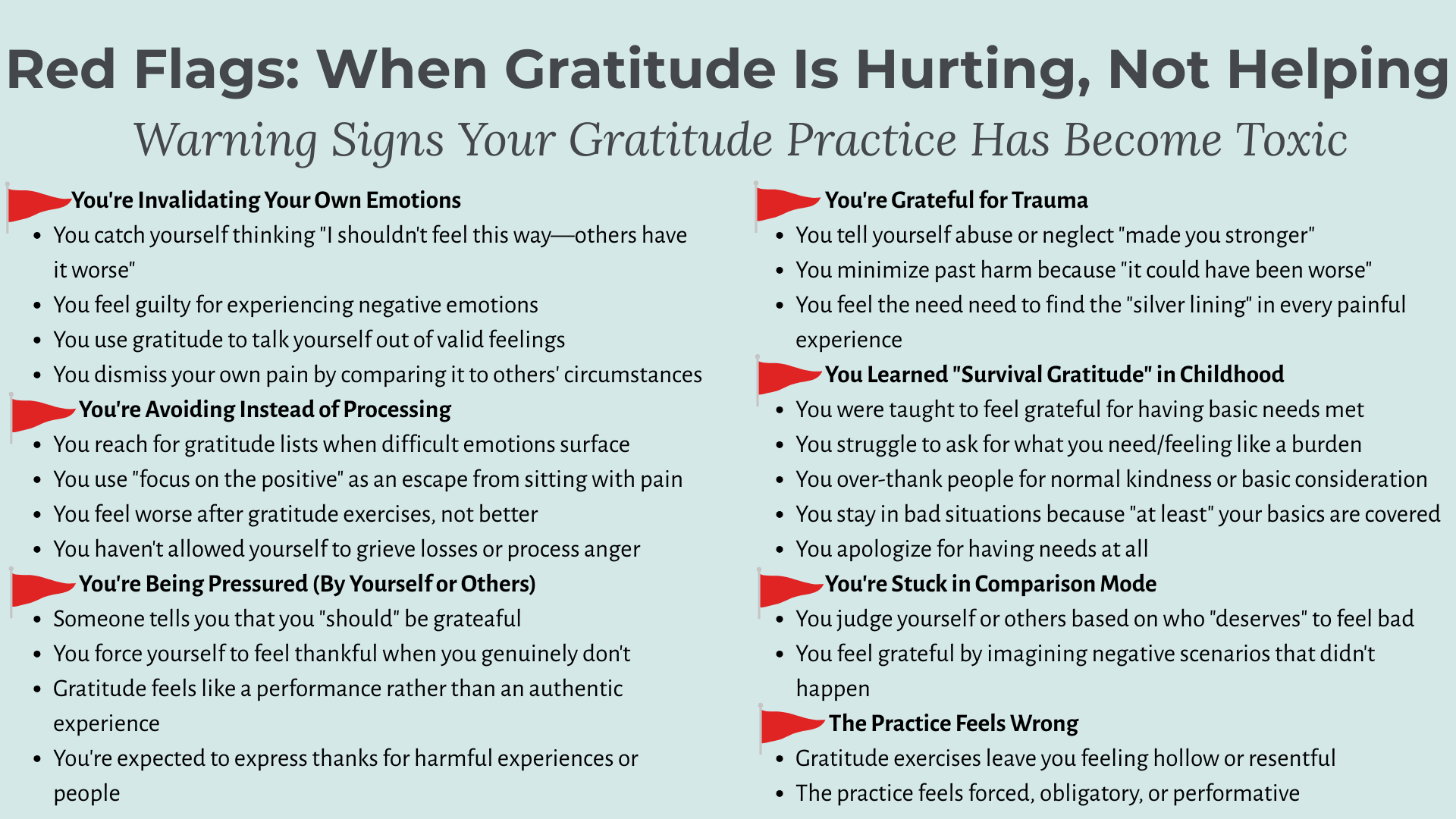

Here's what to watch for:

You're using gratitude to invalidate your emotions. If you catch yourself thinking, I shouldn't feel sad because other people have it worse, that's a red flag. Gratitude shouldn't be practiced in a way that compares ourselves to others. As Dr. Nekeshia Hammond notes, "You can have both: a strong sense of gratitude along with feelings of sadness, confusion, or anxiety" (Gregory, 2022).

You're forcing positivity to avoid processing pain. Sometimes you need to sit with difficult emotions. Pushing them away with gratitude doesn't make them disappear; it just delays the processing your brain needs to heal. Unprocessed or delayed emotional processing can cause trauma, complicated grief, and various mental health challenges (Gregory, 2022).

You're expected to be grateful for trauma. This is especially damaging for those of us who experienced childhood neglect or abuse. For survivors of complex trauma, forced gratitude can invoke anger and prevent authentic healing. It's counterproductive to push gratitude for harmful experiences onto trauma survivors (Davis, 2021).

A Better Approach

So what does healthy gratitude actually look like?

Feel your feelings first. Process what needs processing. Then, when you're ready, notice what's good in your present life—not as an escape from pain, but as an addition to your full emotional experience.

Focus on now, not then. Be grateful for your current support system, your progress, your daily small victories. You never have to be grateful for past harm.

Skip the comparisons. Instead of "I should be grateful because others have it worse," try simply: "I'm grateful for ___." Your experience is yours alone.

Let gratitude and grief coexist. You can appreciate where you are today while still honoring the pain that brought you here. Both can be true.

Recovery isn't about toxic positivity or pretending everything is fine. It's about building something real—and that includes a gratitude practice that actually serves your healing, not one that silences it.

Ready to Practice Gratitude That Actually Works?

I created a free worksheet called The Both/And Gratitude Check-In to help you put this into practice. It's a two-page tool that lets you acknowledge what's hard AND notice what's good—without one canceling out the other.

References

Confino, D., Einav, M., & Margalit, M. (2023). Post-traumatic growth: The roles of the sense of entitlement, gratitude and hope. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00102-9

Davis, S. (2021, November 15). Complex trauma, false gratitude, and letting go. CPTSD Foundation. https://cptsdfoundation.org/2021/11/15/complex-trauma-false-gratitude-and-letting-go/

Gregory, A. A. (2022, April 19). How gratitude can harm mental health—and ways around it. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/simplifying-complex-trauma/202204/how-gratitude-can-harm-mental-health-and-ways-around-it

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112-127.